Dr. Leo Szilard:

下はアメリカで英語の授業を受けているときに書いた論文です。核兵器開発のためマンハッタンプロジェクトを考案したが、最後まで日本への核爆弾投下を反対し続けたハンガリー物理学者Dr. Leo Szilardについての論文です。戦後80年、Dr. Leo Szilardに敬意を表して、掲載させていただきます。

Challenging Nuclear Weapons with a Razor

Have you ever tried to address a big problem with small power? For example, how about cutting wood up with a razor? It might seem silly because it could be almost hopeless for us to accomplish it. Definitely, it would take us such a long time to do it. Even if we spent whole our life chopping wood with a razor, we might not be able to reach the goal. Therefore, a lot of people would say, “It is impossible”, and then they might never try it. However, it might not be impossible. At least, we would have some opportunity to reach the goal. Here is a person who tried to resolve a big problem with his small power; that is, he tried to resolve the problem of nuclear weapons with one-human’s power. His name is Leo Szilard [1898-1964], who was born in a Jewish family in Hungary. In 1919, he went to study physics with the physicists at the University of Berlin, including Albert Einstein (Bess 30). Although Leo Szilard abandoned physics and started devoting himself to political activities after World War II, throughout his life he feared that nuclear weapons would be abused and directed all his energies to finding a solution to how to deal with nuclear weapons for the sake of world peace.

During World War II, at the same time that his curiosity as a physicist drove him to discover innovations in atomic research, Szilard feared that nuclear weapons would be produced and abused. As early as 1933, when he discovered nuclear chain reactions (Lanouette Genius 105), which were essential to produce nuclear weapons, this conflict arose. In fact, his discovery made him remember “The World Set Free”, which he had read in 1932, a year earlier (Lanouette Genius 134). “The World Set Free”, which H. G. Wells wrote as science fiction in 1914, argues that wars will be unacceptable once nuclear weapons are developed, since they can devastate the world (Wattenberg 44). That is, “The World Set Free” premise is that nuclear energy used in a war would destroy “civilization” and the remaining people would live in a contaminated world (Bess 45). Michael Bess, an assistant professor of history at Vanderbilt University, reports that, although Szilard considered the story fantastic the first time he read it, by 1933 he started to fear that it would be possible to produce and develop nuclear weapons (Bess 45). William Lanouette, a former Washington correspondent for a magazine the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, comments that Szilard’s own work on chain reactions in the fall of 1933 was raising the possibility that the story of the book could be real, not fantastic (Lanouette Genius 134). Indeed, from then until his death, he thought only of nuclear weapons (Lanouette Genius 134).

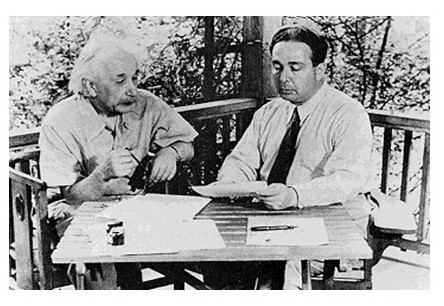

Moreover, this obsession and fear not was just early on, in 1933, but also continued at the next stage of his life as well as he proposed and participated in the Manhattan Project from 1939 to 1945. In 1939, as the problems of nuclear energy were being gradually figured out by the Nazis, Szilard got worried because he feared that the Nazis would use nuclear weapons if they developed the weapons before the allies did (Stoff, Fanton, and Williams 4). This prospect made Einstein and Szilard determined to begin a nuclear arms race with Germany, though it was contrary to his fundamental desire for peace, and to write a letter to President Roosevelt (Lanouette Genius xvi). First, Einstein composed the first short draft of the letter (Lanouette Genius xv-xvi). However, it was Szilard who completed drawing the letter up in detail, explaining the nature of research on nuclear energy and the necessity for funds for the research (Jones 14). Three years later, at last, the letter moved the president to establish the Manhattan Project to produce nuclear bombs (Stoff, Fanton, and Williams 4). Indeed, according to Michael B. Stoff, an associate professor of history at the University of Texas, Jonathan F. Fanton, a chairman of the Board, Human Rights Watch, and R. Hal Williams, a professor of history at Southern Methodist University, “Their [Einstein and Szilard] advice served as an early blueprint for the Manhattan Project” (Stoff, Fanton, and Williams 16). In short, the Manhattan Project was the U.S. government’s confidential project to research and develop nuclear weapons during World War II (Lanouette Genius xvi). Lanouette adds that Szilard decided to prevent Hitler from dominating the world with nuclear weapons by succeeding in the Manhattan Project first (Lanouette Genius xvi).

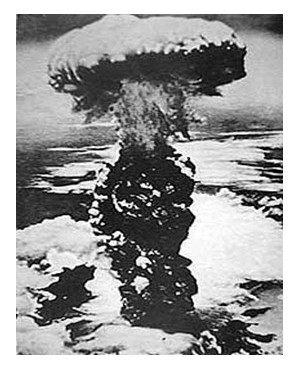

Thus, the fear that the Nazis would succeed in developing nuclear weapons caused Szilard to engage in the Manhattan Project. However, his fears were not assuaged after the Nazis surrendered, for the members of the Manhattan Project, including Szilard, began to fear that nuclear weapons might be dropped on Japan. With the surrender of the Nazis on May 7, 1945, at first, Szilard felt that he was emancipated from the fear of the Nazis and the imminence of the nuclear race (Stoff, Fanton, and Williams 136). David A. Grandy, an associate professor of philosophy at Brigham Young University, adds that at that stage Szilard thought that nuclear weapons would not be used in the war because there was no longer a rival trying to develop nuclear weapons. However, Szilard’s old fear of the awesome power of atomic weapons was aroused upon hearing that the U.S. was considering dropping nuclear weapons on Japan (Grandy 93). In sum for Szilard, the goal of the Manhattan Project had been to safeguard against the Nazis developing nuclear bombs; hence, he opposed using nuclear weapons against Japan (Lanpette “Odd” 109). Additionally, Szilard was concerned that dropping nuclear weapons on Japan without any announcement would cause problems of human morality as well as of postwar nuclear arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union (Bess 48). The arms race might not stop until occurrence of nuclear war (Bess 48). Barton J. Bernstein, aprofessor of history at Stanford University, confirms this point by saying that Szilard believed that nuclear weapons should not be used not only because innocent Japanese civilians would not be killed but also because the U.S. would avoid a potential arms race with the Soviet Union after the war (Bernstein Voice 12). That is, after the surrender of the Nazis, Szilard and other members of the project were still worried that a terrible abuse of nuclear weapons was about to occur (Grandy 94).

Owing to the fear of the possibility of dropping nuclear weapons on Japan, Szilard contributed to the “Report of the Committee on Political and Social Problems, Manhattan Project ‘Metallurgical Laboratory’ University of Chicago, June 11, 1945” called the Franck Report. The report came out of a committee to examine the moral issue of using nuclear weapons (Grandy 94). Grandy explains further that Szilard and like-minded colleagues had formed the committee to provide a forum to discuss how they ought to deal with the ethical issues raised by nuclear weapons (Grandy 94). The committees’ stance was that the government should demonstrate the awful power of nuclear weapons to Japan in an uninhabited area before the government dropped the weapons on Japan. The advantage of this approach was that, in case Japan still did not surrender, the U.S. could resort to the weapons later. Moreover, in this way, the world would see how nuclear weapons could be used ethically in the post-war period (Grandy 94). Matt Price, a graduate fellow of the National Science Foundation, summarizes the first argument of the Franck Report, namely, that a nuclear arms race following the war would happen at high rate even though the nuclear information was confidential; hence, the government should have to try to reach international agreements on the arms control (Price 240). The report bolstered this argument by claiming that dropping nuclear weapons without any announcement would cause difficulties in realizing the international agreements; in contrast, if the U.S. took the high road and overly “demonstrated” the power of the weapons rather than using them, it would be highly possible to reach the international agreements to prevent an atomic arms race (Price 240-241). Especially, Szilard feared a runaway arms race with Russia (Lanouette Genius xvii). In short, the Franck Report was brought by fear that using nuclear weapons would cause to destroy relationship among all nations (Stoff, Fanton, and Williams 136).

Although Szilard worked hard as a physicist during World War II, he abandoned physics after the war both due to the influence of money on physics and due to political reasons. First, the dependence of physics on money, as it required ever more complex machines caused him to become dissatisfied with physics. Szilard gives his ideal of science as creative exploration:

The creative scientist had much in common with the artist and the poet. Logical thinking and an analytical ability are necessary attributes to a scientist, but they are far from sufficient for creative work. Those insights in science that have led to a breakthrough were not logically derived from preexisting knowledge (quoted in Salk xiii-xiv).

However, Grandy reports that Szilard, like other physicists, thought that physics had come to rely on machines operating at ever higher power, to discover “some new particle” (quoted in Grandy 122-123). In “Talk Given at University of Colorado Medical School” on November 11, 1950, Szilard expressed his dissatisfaction with physics new dependence on financing:

A physicist had to go to the army or navy to get himself a million dollars or if necessary ten million, and build a cyclotron for a few hundreds million volts at least … or even ten billion volts, and after he had gone through the trouble of spending several million dollars, which usually takes a few years, he can then sit down and observe phenomena which no one can predict and about which he can be astonished (quoted in Bess 56).

According to Grandy, that kind of physics never satisfied Szilard (Grandy 123) because he seemed to find a gap between his ideal above, creativity, and the reality. In other words, Szilard seemed to feel that physics had lost its ability to be creative.

Second, besides the dependence of post-war physics on expensive machines that precluded independent creativity, there were two political reasons that Szilard abandoned physics. One crucial reason was that the extreme compartmentalization. “Compartmentalization”, a military term, enforced as much separation of the members of the Manhattan Project from one another as possible to secure top secrets; that is, it was the nature of nuclear research at that time (Stoff, Fanton, and Williams 4). In this situation, the members of the project, accordingly, were not allowed to freely discuss their research (Stoff, Fanton, and Williams 4). In fact, government agents even spied on the project members, for example, monitoring their phones, confirming contents of their letters, and even worse following them on leave (Stoff, Fanton, and Williams 4). Jones confirms this point by saying that the members were allowed to receive information from the other members only when they absolutely needed the information for their goal; however, even when permitted to know information, they were allowed to access only “the minimum necessary” (Jones 268). For this reason, it was impossible for the scientists to know about other scientists’ working (Cathcart 34).

Szilard saw this extreme compartmentalization of all work in physics as counterproductive and inefficient research. According to Vincent C. Jones, a historian on the staff of the U.S. Army Center of Military History, various scientists in the project, including Szilard, objected to the extreme separation (Jones 209). Szilard felt that the method wasted both money and time (Stoff, Fanton, and Williams 4). In truth, other scientists agreed with his criticism. As a result, Szilard together with the scientists appealed to the government, arguing in a series of letters that the nuclear research should be more controlled by the scientists (Price 228). In particular, a memorandum in May 1942, Szilard argued that the compartmentalization was interfering with the progress of the research (Price 231). In December 1943, he complained to the government about the compartmentalization again, saying that many of the labs in the project shared his “dissatisfaction” (Lanouette Genius 255). Szilard seemed to struggle to improve the situation of extreme compartmentalization, throughout the Manhattan Project. Grandy confirms this point by saying that Szilard felt as if the government had the scientists in their hands and that the government did not allow them to participate in decisions related to their own work (Grandy 101). Szilard complained that “political interests” had clearly interfered with physics (Grandy 119).

Besides compartmentalization, the other political reason that led to Szilard’s decision to abandon physics was the government’s decision to drop nuclear weapons on Japan over scientists’ objections. Szilard philosophy was, “Do not destroy what you cannot create” (quoted in Lanouette Genius 203). However, the nuclear weapons he had made were “destroyed” by the government in August 1945 over Japan. In truth, he had tried hard to prevent nuclear weapons from being “destroyed” by being dropped on Japan (“Szilard Interview”). In an interview in 1960, Szilard said that he thought the government did not carefully examine whether they should use nuclear weapons or should do something else to end the war. They just wanted to bring an end to the war by the use of the weapons (“Szilard Interview”). In truth, even Oppenheimer, a member of a government committee to examine how to handle nuclear issue, complained about Szilard’s actions against using nuclear weapons, arguing that scientists should not have any power to decide political issues (Lanouette Genius 270). For this reason, the Franck Report, the petition against dropping the nuclear weapon, was not approved by the government committee (Lanouette Genius 268). As a result, when nuclear weapons were dropped on Japan in August 1945, Szilard felt as if he bore all responsibility (Bess 42). Meanwhile, he felt that physicists were not allowed to influence decisions of public policy at all (Grandy 101). Szilard writes on this point,

As far as I can see, I am not particularly qualified to speak about the problem of peace. I am a scientist, and science, which has created the bomb and confronted the world with a problem, has no solution to offer to this problem (Szilard “Crusade” 7).

After the bombs were dropped, Samuel K. Allison, one of Szilard’s colleagues, commented “Dropping the bomb on Hiroshima was a tragic mistake. Dropping the bomb on Nagasaki was an atrocity” a sentiment which Szilard later echoed (quoted in Lanouette Genius 277). All in all, it seems that Szilard felt a profound sense of powerlessness because of the fact that he was not able to change any decisions of the government as a physicist. On June 1, 1946, Szilard left his laboratory (Lanouette Genius 312).

After Szilard abandoned physics because of both the influence of money on physics and political reasons, the fear of a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union caused him to devote himself to working for peace as an advocate of international cooperation and nuclear arms control. First, in the late 1940’, he wrote some articles in a magazine “Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists”. In one of the most famous of these “Calling for a Crusade [in 1947]”, Szilard explains the cause of a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union and the impediments to peace. That is, the cause of the race was the fact that, although they both were unwilling to have war, neither wanted to lose any war that might come along; however, in this situation, only if the two countries changed their policies led by “such considerations”, they would find ways to ease the impediments to peace (Szilard “Crusade” 8). Specifically, to address this problem, Szilard proposes in the article:

At present we propose to eliminate atomic bombs from all national armaments by setting up an international control agency, and we offer to the Russians, as the main inducement, to discard our own bombs at an early date and thus to free Russia from the danger of being attacked (Szilard “Crusade” 10).

In conclusion, in the article, he said that the U.S. needed to start “a crusade for an organized world community” as soon as possible; otherwise, nuclear war would break out (Szilard “Crusade” 19-20). It seems that Szilard wrote this article to the U.S.

In addition to “Calling for a Crusade”, which seems to be written to the U.S., Szilard wrote another famous article “Letter to Stalin [in 1947]”, which gives his analysis of what the Soviet Union should do to ease a nuclear arms race. Szilard, in fact, wished that he could have sent this article directly to Stalin, the premier of the Soviet Union; however, he could not because it would not have been illegal to do so. As a result, instead of sending it to Stalin, the article was run in “Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists” (Bernstein Livable World xli). In the “Letter to Stalin” Szilard begins by saying he seriously feared that relationship between the U.S. and the Soviet Union would become worse (Szilard “Stalin” 26). Then Szilard told Stalin that, if the Soviet Union desired peace, there were ways for Stalin to break the difficulty between the two countries if “diplomacy” was abandoned (Szilard “Stalin” 27). Instead, regarding the resolution, Szilard suggests that, first, Stalin precisely give speeches setting forth his general foreign policy for peace in as much detail as possible so that Americans could understand (Szilard “Stalin” 29). That is, the article, which proposed improved and open communication between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, was written to prevent the Cold War from heating up (“The Register”). In short, Szilard proposed that Stalin announce his ideas and suggestion about peace to directly people in the U.S.

(Bernstein Livable World xli).

Indeed, Szilard wrote not only articles but also science fiction to make his ideas appeal to more people. One of the most famous of these is “The Voice of the Dolphins”, which presents his hope and proposed course to world peace. The story line is that the U. S. established the “Vienna Institute” together with the Soviet Union to research communication between scientists and “super intelligent” dolphins. Amazingly the dolphins developed “plans” for international demilitarization and got the two sides to communicate and negotiate, leading to a new demilitarized world (Bess 61). The dolphins had the ability to do all this intelligent because the scientists taught the dolphins science and world politics after the discovery of ways to communicate with the dolphins (Grandy 126). The dolphins worked with the scientists very well. As the result, although there was danger of war, world peace continued for thirty years (Grandy 126). Of course, Bess explains, at the end of the story, the narrator concludes that the scientists made up the existence of the super intelligent dolphins and were trying to improve their own “credibility” as peace advocate through the imaginary dolphins (Bess 61). In short, Szilard seems to be saying in this little fable that the scientists were able to participate in the decisions of politics only through the fiction of the dolphins, not directly as scientists. Szilard wrote;

Political issues are often complex, but they are rarely anywhere as deep as the scientific problems which were solved in the first half of the century. These scientific problems were solved with amazing rapidity because they were constantly exposed to discussion among scientists, and thus it appears reasonable to expect that the solution of political problems could be greatly speeded up … if they were subjected to the same kind of discussion. (Quoted in Bess 84)

The book presents “what such a world might look like” and “the change that would have to occur” so that we advance world peace (Bess 63). Bernstein sums up “The Voice of the Dolphins” holds unstable “nuclear stalemate”, “live with the bomb”, and a path from danger of nuclear war to world peace (Bernstein Voice 4).

Besides writing articles and books, in 1960, Szilard informally met Khrushchev, the premier of the Soviet Union, as part of his efforts to establish friendly relations between the U.S. and the Soviet Union and to prevent a nuclear arms race and nuclear wars. In the meeting, he offered two gifts and his ideas. One of the gifts was “The Voice of the Dolphins”. When Szilard gave the book to the Soviet leader, Szilard told him that he had written the book to show how atomic situation worked and how the situation might improve in the arms race as time passed (Lanouette Genius 420-421). According to Bernstein, Khrushchev swore to Szilard that he would read the book as soon as it was translated to Russian (Bernstein Voice 40). The other present was a razor called the Schick Injector, which was inexpensive but well designed (Quoted in Lanouette Genius 415). In Grandy’s analysis, the gift was intended to present the contrast between a small harmless tool and a huge lethal tool: between the razor and a nuclear weapon. It was more than a token of friendliness (Grandy 125). In Bess’s analysis, because of the long conversation between Szilard and Khrushchev, it is implied that the leader of the Soviet Union caught Szilard’s “device” of the razor and “the political wisecrack”; therefore, Khrushchev considered Szilard as not a political partisan but a real advocate for peace (Bess 72).

In addition to the two gifts, Szilard proposed his ideas directly to Khrushchev in the meeting. According to Bess, when he met with the leader of the Soviet Union, he offered three main points. First, he suggested that the Soviet Union maintain reasonable communication with the U. S. Second, he suggested that a direct phone called the “Moscow – Washington Hotline” be established so as to be able to immediately communicate in an emergency. Last, he suggested that, through better communication, including the hotline, the two countries resolve the problem of nuclear weapons and find a way to peace (Bess 72). Lanouette reports that Szilard suggested the hotline not only because it could be helpful if a crisis happened but also because it would keep the two countries reminded of their fear of weapons. Evidently the leader of the Soviet Union agreed with Szilard’s idea (Lanouette Genius 419). Bess confirms this point by saying that Khrushchev responded that he would be pleased to set up the Kremlin– White House hotline if the U.S. president agreed to it (Bess 72). Three years after the meeting, the hotline came true (Lanouette Genius xvii-xviii). Lanouette adds that Szilard fundamentally hoped that reduction of nuclear weapons would be based on improved trust between the two countries (Lannoette Genius 420).

Why did Szilard give the Schick Injector razor to the leader of the Soviet Union? Why not scissors? Scissors are, likewise, a cutting tool with blades. Indeed, when Szilard started political activity after the war, his mentor Einstein said to Szilard as well as other scientists, “You must not use razor blades for chopping wood, …” (Quoted in Lanouette Genius 363). Einstein appeared to believe, “It is impossible for us to cut wood up with a razor”. However, regardless of the warning of the genius, it seems to me that Szilard accepted the challenge to “cut wood up” with “a razor”, as he acted so long and so hard both out of his fear of nuclear weapons and hope for peace.

Nobody should renounce even the boldest hopes before human nature had been given every opportunity to demonstrate its limits.

--- Leo Szilard, 1930---(Quoted in Bess 41)